By Lisanne Renner

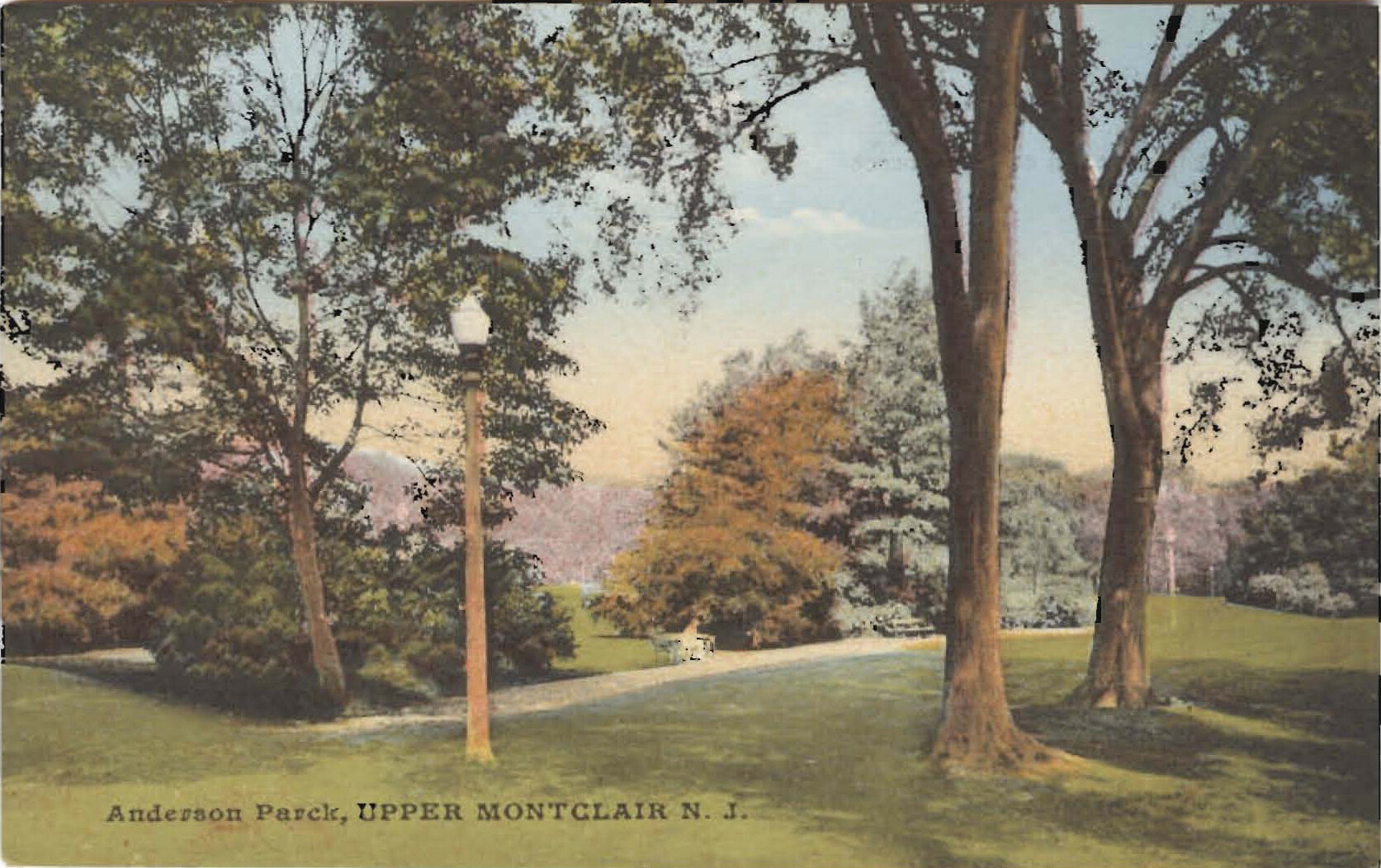

As workers were deep in dirt creating Essex County’s Anderson Park in 1904, Montclair’s civic leaders eyed that transformation and called for a townwide park system.

The ills of New York’s congested squalor felt uncomfortably close as a Montclair citizens’ committee formed that year to push for parks. Town leaders viewed parks as “beauty spots,” akin to grand civic buildings embraced by the City Beautiful movement. And they also saw them as healthful “breathing spaces” during a time when tuberculosis ran rampant.

When the committee formed to identify potential parkland, Montclair residents had only 14-acre Anderson Park (under construction), four-acre Rand Park, and tiny Crane Park. Private athletic fields were for members only. Just one playground served the town’s 3,000 schoolchildren.

While Montclair was growing fast as a railroad suburb, the committee wanted to preserve at least 75 acres for parks. In 1905, one committee member, William B. Dickson, a U.S. Steel Corporation executive, bought 13 acres of woods to set aside until the town could buy them. His effort was not purely beneficent: He wanted to thwart a move to build homes for African-Americans on land that is now Nishuane Park, fearing, he said, “an invasion of what was supposed to be a rather exclusive residential section of the town.”

The committee selected three more potential parks: Edgemont, Glenfield, and Essex Park and Essex Field (now Woodman Field). Eight committee members, many of them wealthy businessmen, agreed to underwrite the bond issue required for the town to buy those sites. A special election was set for April 10, 1906, to vote on the proposal.

What’s not to like about parks? Plenty. Opponents included those averse to the taxes a bond issue would bring, disenfranchised black voters, and women opposed to taxation without representation. Supporters tended to be businessmen, doctors, realtors and developers. Their motivations ranged from altruistic to pecuniary.

The lead-up to Election Day was intense. Heard repeatedly among advocates was the call for “breathing spaces.” Jacob Riis, the urban reformer who had documented wretched New York slums, visited the Commonwealth Club days before the election to endorse the parks proposal: “We expect – the country expects – Montclair to do its duty in this matter, which is to provide both parks and playgrounds for the people, big and little.”

About a quarter of Montclair was made up of Italian immigrants and African-Americans often living in substandard conditions. These were among the people Dr. Martin J. Synnott expressed concern for when he advocated park acquisition, mentioning the needs of “the poor mother airing her sick baby in the summertime.”

Unswayed by such heartfelt rallying cries were opponents who crossed racial, gender and economic lines. Some voiced concern for the modest tax increase that would result from a bond issue. Women, not yet allowed to vote, resented that they had no voice in how their taxes were spent. Signing a letter to the editor as “A Woman Taxpayer,” one opponent wrote to The Montclair Times: “There is a large number of persons who are denied representation and have no way to protest a measure which may cause them real inconveniences.”

And African-Americans rejected the proposal almost unanimously. They feared rent increases and they felt disenfranchised. As the Rev. John Love, a pastor at the Union Baptist Church, put it: “It seems to be the desire of the people back of the park movement to make Montclair a town where it will be impossible for a poor man to live, except as a laborer or house servant.”

Vigorous debate led to a large voter turnout that day in 1906. “The election was close and for a time it looked as if the opposition would carry the day,” The New York Times reported. “But the friends of parks and playgrounds, many of them prominent New York business men, got out their carriages and automobiles, and with the help of thousands of ‘dodgers’ and handbills, secured enough votes to overcome the heavy opposition.”

More than a century later, Montclair has 142 acres of its own parks, preserves and playing fields. Its borders also touch or include more than 700 acres of Essex County parkland. For a town that has more than doubled its 1906 population, that is a goodly supply of breathing space and beauty spots.

The Montclair History Center invited Lisanne Renner, historian for Friends of Anderson Park, to contribute this article, which first appeared in the June 2020 issue of Montclair Neighbors. More about Anderson Park is at FriendsOfAndersonPark.com and on the conservancy’s Facebook page.

Essex County’s Anderson Park opened in 1905 and provided the impetus for Montclair’s townwide park system. Credit: A. Tucoulat, via Friends of Anderson Park Collection

This postcard shows Anderson Park around 1907. The sender wrote, “Montclair is a very pretty place, very thick with trees.” Credit: F.W. Poecker, Stationer/Friends of Anderson Park Collection

The realtor Frank Hughes promoted Montclair’s parks in his 1913 brochure, “Montclair, N.J., and Its Advantages as a Place of Residence.” Credit: Frank Hughes